Kate Lamble

Presenter, Derailed: The story of HS2•@katelamble

BBC

BBC

"I can't answer those questions currently," says Lord Peter Hendy. More than 15 years have passed since the idea to build a high-speed railway up the west coast of England was first announced, and I am asking the rail minister when it will be finished. And, crucially, how much it will cost.

Only he is making it very clear that nobody knows what the final bill for Britain's biggest infrastructure project might be. Does it concern him that the government remains committed to the railway despite this deep uncertainty? I ask. "Oh yeah, we're dead bothered by that. Of course you would be..."

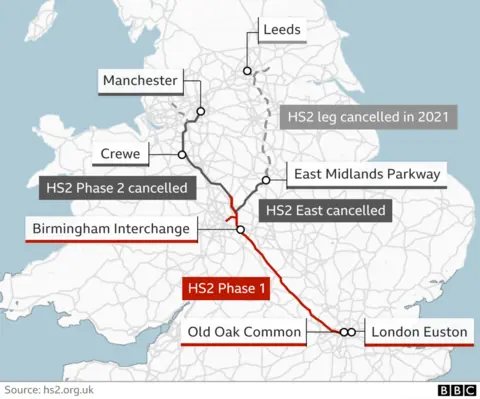

Currently tens of billions of pounds over budget and around a decade behind schedule, the Public Accounts Committee describes High Speed 2 (HS2) as a casebook example of how not to run a major project.

Reports state that the now shortened line between Birmingham and London could cost £81bn. Accounting for inflation, that would mean at least £100bn will be spent, but only 135 miles of railway built. Many people involved - from civil servants, ministers and company insiders to HS2's original designers - have told me just how badly things went wrong.

Certainly, the project has suffered from mismanagement, misplaced optimism and failures when dealing with homeowners whose properties were in its path.

PA Media

PA Media

HS2 Ltd, the company created by the Department for Transport, accepts it failed to keep costs under control

But one chartered surveyor, who has been challenging HS2 for almost a decade, brought up another point. One that suggests that - far from this solely being down to poor decision-making - something greater was at play all along.

"There has always been a fundamental problem in this country with the cost of building anything," the surveyor says, "because we live on a small, highly populated, property-owning, democratic island."

Which begs the question, was HS2 predestined to encounter major problems simply on the basis of the UK's geography and political system? And if that is the case, where should we go from here?

Problems with the need for speed

HS2 was initially conceived as a way to increase capacity on the West Coast Mainline; a tangled 700 miles of track between London and Glasgow, which was built in a patchwork fashion by competing Victorian entrepreneurs.

High Speed 2's early engineers proposed a vision of the future, making HS2 capable of running the fastest, most frequent trains in the world.

Sized up alongside the international alternatives, the plan was impressive: in France, high-speed trains run at 200 miles per hour; HS2 was to be built to withstand 250mph. In Japan, 12 trains run between Tokyo and Osaka every hour; HS2 would be capable of running 18 trains an hour going in and out of London Euston in that time. That's one every three minutes.

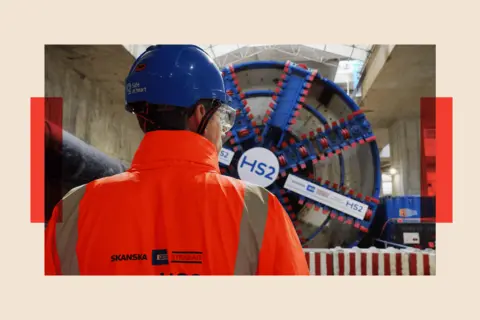

HS2 Ltd

HS2 Ltd

HS2 was to be built to withstand speeds of 250mph

To have any chance of doing this, however, the railway had to be as straight as possible. Slowing down to take bends around villages, woodland or canals wasn't an option. Faster trains also required more sophisticated junctions, and stronger slab track.

But government reviews now suggest this ambition had an insidious cultural impact - and that the vision to build the best possible line is what "drove the scope and dramatically increased cost.

"It also took the project away from the initial premise of increasing network capacity."

Andrew Meaney is head of transport at the consultancy Oxera and advised the Oakervee review of HS2 that reported to government in 2020.

Andrew suggests no analysis was done to set out comparisons of what the savings would be if trains ran at the slower speeds of Eurostar services in the south of England.

"I think those sorts of things should have been assessed in quite a lot of detail and a public conversation had about those trade-offs."

A warning from the French

But talking to HS2's original designers, there was a clear strategy behind this vaulting ambition.

Andrew McNaughton, HS2's first technical director, remembers being at a conference in 2009 and hearing the chair of the French railway operator, Guillaume Pepy, deliver a warning.

That is: "don't make the mistake of building yesterday's railway", with standards evolving, French high-speed trains could now go much faster than their tracks would allow.

Why bother building something that would already be out of date at the moment of completion?

Mr McNaughton decided to future-proof the UK work by selecting an option that appeared capable of handling faster trains further into the future.

He understood that this would add roughly 10% to costs - and believed it would be worth it.

'You've cost us another hundred million'

As politicians set about trying to get approval to make HS2 run straight and fast, they came across another obstacle.

Much of the route cut through rural constituencies, represented mostly by Conservative MPs, who made it clear to then-Prime Minister David Cameron that their approval for the project would require serious negotiation and compromise.

Ministers picked something unusual to make it happen: a hybrid bill, only the third of its kind enacted since 1992.

These allow MPs to vote on whether a piece of infrastructure should go ahead, but those directly affected are given the right to petition against it and ask for details to be changed.

Reuters/Toby Melville

Reuters/Toby Melville

HS2 had to run through mostly Conservative rural constituencies, where many MPs told David Cameron they'd only support it if major compromises were made

Councils, businesses and individuals made their case in front of a government committee asking for everything from noise barriers to financial compensation for communities losing green space. Last-minute negotiations often took place in the corridors outside.

The approach meant the bill was flexible - but critics have argued it was also needlessly complex and expensive.

Sir Geoffrey Clifton Brown was a Conservative MP and was one of the committee members who heard out petitions. "I remember very clearly one of the Secretaries of State for Transport, after an afternoon session, say, well done, Geoffrey, you've just cost us another couple of hundred million this afternoon."

A spreadsheet shows the thousands of assurances which were added as a result - among them, £250,000 to insulate a church, £500,000 for a new park (on top of an extra £10m for a community fund), as well as £10,000 to renovate a listed drinking fountain.

Vast cost was added in order to avoid or compensate for individual inconvenience.

PA Media

PA Media

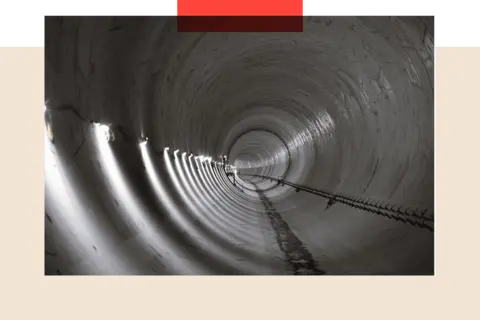

Tunnels and noise barriers were the most expensive parts of HS2

One of the most expensive parts of these measures were the tunnels. Through public consultation and the hybrid bill, the design now features so many of them - along with noise barriers and cuttings, where track is laid below ground level - that on a 49-minute journey from London to Birmingham passengers will only have a view of the countryside for nine.

HS2 Ltd, the company created by the Department for Transport, accepts it failed to keep overall costs under control and says delivery has not matched what it describes as the unrealistic early expectations.

Is the UK planning system to blame?

Negotiation and compromise however, worked. The final vote for the first leg of HS2 between London and Birmingham was won by more than 350 votes in October 2013. The bill was supported across the main parties, and ministers understood HS2 had a clear road ahead.

"I was told that [the bill] basically gave the planning approval," says Patrick McLoughlin, who was the Transport Secretary between 2012 and 2016.

"Of course, it subsequently turns out that that was not the case."

PA Media

PA Media

MPs backed the first part of HS2 with cross-bench support from Conservatives, Labour and Lib Dems

In reality, the hybrid bill only offered "deemed planning permission" - HS2 say they have since needed to acquire more than 8,000 further permissions from councils and other agencies.

It hasn't always been given.

Take the case of Dobbins Lane in Buckinghamshire. In April, the local council considered planning permission for HS2 to upgrade a farm track running into a nearby field. This work was needed in order to build an underground box to monitor groundwater levels, which in turn was a requirement of a tunnel being dug through the nearby hills. Without it, HS2 warned, delays could cost tens of millions.

But more than 800 local residents signed a petition against works because of a temporary increase in road traffic: 60 lorries would need to reach the site during a 12 week period.

And the request for planning permission was rejected - another potential cost added.

NurPhoto via Getty Images

NurPhoto via Getty Images

Ed Lister, who worked as Deputy Mayor of London and later as Boris Johnson's chief of staff, says the planning system is to blame

Ed Lister, who was Deputy Mayor of London between 2011 and 2016 and later served as Chief of Staff to Prime Minister Boris Johnson, blames the UK's planning system.

"You've got to break that log-jam," he argues. "If these are your big projects, then they have to go through."

He wants changes to the judicial review system to make it harder to frustrate projects such as HS2 through the courts.

Big questions to be confronted

All of this is a reminder that building in Britain has always had its own unique challenges. France, for example, has more than 1,000 miles of high-speed rail - but it also has a greater land mass, with much more open empty countryside to sweep through.

China, meanwhile, has nearly 30,000 miles of high-speed rail - but it also has a centralised power system and fewer protest rights.

Which brings it back to the chartered surveyor who observed, "We live on a small, highly populated, property-owning, democratic island".

That in itself poses challenges - meaning that if Britain wants to build 'big' - whether it's a nuclear power station, reservoir or railway, we need to confront big questions as a society. How deep is our appetite for individuals to have their lives impacted in the name of national interest? How should we value century long investment in infrastructure? These are the questions that govern how our system works.

"The processes that we've got are so archaic and too costly and too complicated. There's surely got to be a quicker way of doing it," says the chartered surveyor.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Andrew McNaughton is optimistic: "When it's opened… I still believe that people will go, oh, for heaven's sake, let's just get on with the rest of it"

For Andrew Meaney, a fundamental problem is the way politicians communicate with the public.

"We don't have the confidence to say, right, this is what we're building and let's just go and get on and build it," he argues. "We tend to change our mind and we sort of bend with public opinion."

For others, all these existential questions will always be secondary to the fact they think HS2 was simply the wrong project. "You've got to choose the right projects," argues Andrew Gilligan, who acted as a special advisor to Boris Johnson and Rishi Sunak. "And this was the wrong project right from the start."

"The answer to our transport crisis is lots of boring little things like bus lanes and tram systems and new stations," he continues, "and not one grand mega-project that is in fact only going to touch a handful of people in the country."

If future governments did decide that small was the way forwards, the same fundamental issues of consent and compromise would still be ever present. Without answers HS2 will remain simply the latest project to be undone by political reality.

Top image credit: Christopher Furlong via Getty

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

.png)

4 months ago

12

4 months ago

12

English (US) ·

English (US) ·