James GallagherHealth and science correspondent

James Gallagher

James Gallagher

James Gallagher, health and science correspondent

Is curing Alzheimer's disease an impossible challenge or can we get there?

To find out I've been invited to watch brain surgery at the cutting edge of dementia research.

I'm wearing scrubs at the back of an operating theatre at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. The intense focus of the dozen people in the room radiates an aura of calm despite the cacophony of medical machinery beeping and pumping away.

The patient is sedated and covered up on the operating table. On the large screens above I can see the MRI scan of his brain. It is impossible to miss the large, bright white mass of a tumour. The cancer had started in his colon before spreading deep inside his brain.

"It's not on the surface of the brain so we need to make a hole in the cortex," Prof Paul Brennan, professor of neurosurgery tells me, "as small as possible, but large enough that we can get down towards the tumour".

The cortex is the outer layer of the brain involved in language, memory, and thought. The inner parts of the brain are softer, but the cortex has to be cut through.

Prof Brennan uses a surgical drill to remove a flap of skull. The exposed brain is pink, flushed with blood, and gently pulsing to the beat of the heart.

Standing next to me is Dr Claire Durrant, an Alzheimer's researcher at the University of Edinburgh.

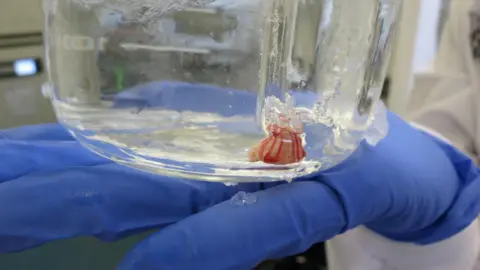

She's holding a container of ice-cold, artificial cerebrospinal fluid, which mimics the liquid that bathes the brain and spinal cord.

In most brain surgeries the removed section of cortex is medical waste and would be binned. But Edinburgh is one of only a handful of centres around the world where it is collected, with permission, for dementia research.

When the moment comes, it is quick. Prof Brennan places a section of brain - about the size of my thumb nail - into the jar to sustain it.

James Gallagher

James Gallagher

A small piece of brain tissue kept inside ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid.

Then, with a quick thank you, we're getting changed and travelling across the city to the university.

In the back of the car it strikes me how, just minutes ago, this piece of brain was still a part of a man's thoughts and fears of the surgery he was about to face.

"I'm always aware - every time - what we're getting is a precious gift on what is probably the worst day of that person's life," Dr Durrant tells me.

Her lab is one of the few to work on living adult brain tissue to try to understand dementia and other diseases.

"By developing these techniques we hope we're going to move forward to a world free of many different, horrible neurological diseases," she says.

Around one million people in the UK have some form of dementia, with Alzheimer's being the most common.

But can it ever be cured? That was the question set by the inventor Sir James Dyson who is guest editing BBC Radio 4's Today programme on Boxing Day.

James Gallagher

James Gallagher

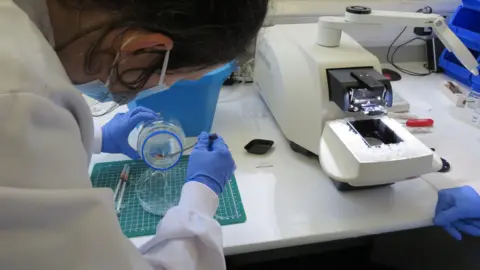

The brain tissue is removed from the container...

James Gallagher

James Gallagher

... and will be set in agar jelly to hold it in place...

James Gallagher

James Gallagher

... before being delicately cut into slices thinner than a human hair

Dr Durrant's laboratory team are trying to figure out the answer by understanding the fundamental biology of Alzheimer's.

There are still crucial unknowns - there isn't a definitive explanation of why the connections between neurons, called synapses, are lost in Alzheimer's.

The four scientists preparing the brain tissue in the lab work in synchrony like a pitstop team - which is very on brand as the research is sponsored by the Race Against Dementia charity set up by Formula 1's Jackie Stewart.

First, the brain sample is set in jelly. Next, it is cut into slices 10-20 brain cells deep, before being stored in specialised incubators to keep the tissue alive.

The team are then exposing the brain slices to toxic proteins called amyloid and tau, which build up in the brains of people with Alzheimer's disease. It allows them to witness the destruction of synapses and see if there is a way of stopping it.

Everything Dr Durrant is seeing so far convinces her that curing Alzheimer's is not an impossible challenge.

James Gallagher

James Gallagher

Dr Claire Durrant says there is more hope than ever in Alzheimer's research

"The evidence we have at the moment is that it is a disease, and that we know from past experiences that disease can be cured. Maybe one day we'll find evidence that Alzheimer's disease is inherently part of being human, but at the moment I don't see that," says the Race Against Dementia Dyson Fellow.

"I've not seen so much hope in Alzheimer's disease research than I do right now. I'm really hopeful we'll see meaningful change in my lifetime."

Glimmers of hope came from two drugs – called lecanemab and donanemab – that slow the pace of Alzheimer's disease.

They were a scientific achievement, however their real-world impact in patients has been labelled by some as too small to be noticeable. Neither is funded by the NHS.

But Prof Tara Spires-Jones, director of the Centre for Discovery Brain Science at the University of Edinburgh, thinks these two drugs have "really opened the door" for cracking Alzheimer's.

James Gallagher

James Gallagher

Prof Tara Spires-Jones predicts there could be life-changing developments in the field

She greets me from behind a giant theatrical curtain in her lab. It is blocking out the light so she can work at a highly-sensitive confocal microscope that uses lasers to illuminate brain samples.

She's studying the role of star-shaped immune cells, called astrocytes, in Alzheimer's.

It is part of a growing acknowledgement that Alzheimer's may need to be tackled from multiple directions.

Lecanemab and donanemab both target the toxic sticky protein called amyloid. Clinical trials of drugs targeting the other protein tau are under way.

And the importance of the immune system, inflammation, the health of your blood vessels and how genetics and the environment combine are all furthering understanding of Alzheimer's.

Prof Spires-Jones thinks there will be three key moments:

- In the short term, drugs that meaningfully slow or stop the progression of the disease

- Tools for preventing dementia entirely

- And, in the long term, a way of curing those who already have symptoms - although she acknowledges that will be much harder.

She thinks we are five to 10 years away from a treatment that is "truly life-changing" and we will get to the point where we can "really make your life normal" by catching the disease early enough and then halting it.

But while there is optimism, it will still need research and clinical trials to prove that curing Alzheimer's is possible.

"The human brain is so phenomenally complex that we really just have to see it in people," Prof Spires-Jones says.

To listen back to the full BBC Radio 4 Today Programme Guest edit with Sir James Dyson head to BBC Sounds.

The Today programme Sir James Dyson guest edit was produced by Laura Cooper.

.png)

3 hours ago

2

3 hours ago

2

English (US) ·

English (US) ·