Joshua Nevett

Political reporter

PA Media

PA Media

Trapped in underground rocks, a potential energy resource has eluded generations of British politicians.

It's called shale gas and the method of getting it out of the ground, known as fracking, has proved politically difficult.

Fracking, short for hydraulic fracturing, has been banned many times by different prime ministers since 2011 over concerns about earthquakes and environmental impacts.

And yet despite this, Reform UK - which is leading in national opinion polls - believe it's worth going after the gas again.

"We've got potentially hundreds of billions of energy treasure in the form of shale gas," Richard Tice, the party's deputy leader and energy spokesperson, says.

"It's grossly financially negligent to a criminal degree to leave that value underground and not to extract it."

The party led by Nigel Farage is telling energy firms to get ready to "drill, baby, drill" if it gets into government after the next general election.

Reform UK says it's serious about shale - but will its plans succeed where so many others have failed?

The history of fracking in the UK shows it won't be easy.

Shale fail

Fracking has been going on in the British oil and gas sector for decades and largely flew under the political radar until about 2010, when shale gas extraction started taking off in the United States.

At the time, Charles Hendry was the energy minister and at first, he was cautiously optimistic about the prospects for a US-style shale gas boom.

But the abortive fracking efforts of the last decade or so have turned the former Tory MP into a sceptic.

He watched former Prime Minister David Cameron's dash for the gas slow to a crawl after fracking projects were hampered by planning delays, minor earthquakes, legal challenges and persistent protests.

As a result, Cameron's promised "shale gas revolution" never materialised and in 2019, tremors were recorded at a fracking site, leading to a ban.

"When ambition hit reality, it wasn't what people had hoped for," Hendry says. "It is much more difficult than it is in the US. It's more expensive. It's more polluting. It's more disruptive."

The former minister says there was simply less space for fracking in the UK than in the US and consequently more obstacles in the way.

Given the level of opposition to removing those barriers, Hendry says, Reform UK's zeal for shale gas was mistaken.

"Even Reform voters will be up in arms about the idea," Hendry predicts.

The most recent attempt to get fracking going again is another cautionary tale.

When former Prime Minister Liz Truss last lifted the fracking ban in 2022, opposition MPs forced a vote on the issue and although her government won, a major rebellion by Tory MPs shook confidence in her leadership and she resigned the next day.

Her successor, Rishi Sunak, reinstated the moratorium on fracking and now the Labour government says it intends to ban the practice permanently.

So, how would Reform UK navigate this political minefield?

PA

PA

Richard Tice said the UK should be making the most of its gas resources

Firstly, Tice says, Reform UK would lift any fracking ban immediately.

Secondly, he says, a Reform UK government would work with oil and gas companies using new extraction techniques to explore for shale gas at a couple of independently monitored fracking wells.

"That will confirm the quantity of gas available and satisfy people that it's safe," Tice says.

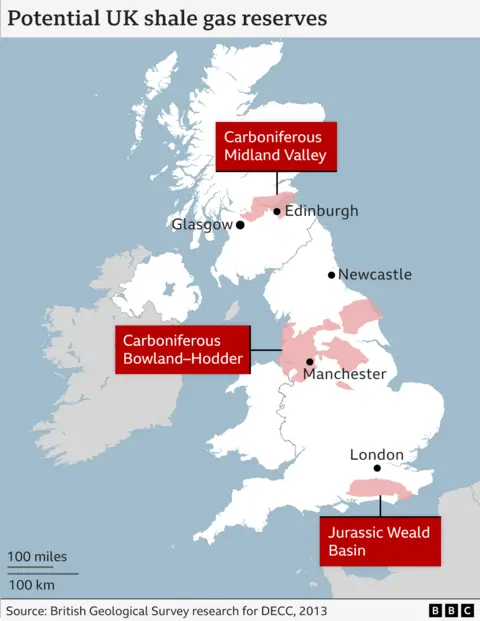

The British Geological Survey (BGS) has identified four areas where there's potential for commercial shale gas extraction, with the largest spanning Lancashire and several countries in the Midlands.

In one prominent 2013 study, the BGS said more testing was needed "to prove that shale gas development is technically and economically viable" in the UK. Even then, the BGS said, "it is far from certain that the conditions that underpin shale gas production in North America will be replicable in the UK".

Despite this uncertainty, Tice is bullish and says they'd know within two years of testing whether fracking for shale gas was worthwhile in the UK.

But unlike Labour, which promised to spend £28bn a year on green energy, Reform UK wouldn't invest any public money in fracking.

"The government's job is to create an attractive regulatory and tax framework," Tice says.

Although the next general election is potentially years off yet, Tice and Farage have already been laying the groundwork for their fracking resurrection in meetings with oil and gas firms.

In one such meeting in Aberdeen, Scotland a few months ago, Tice and Farage told these companies to prepare applications for licences to look for shale gas.

"Don't write off Britain," Tice told them. "Keep us in mind, and in the run up to the next general election, you should be getting your ducks in a row and getting applications ready."

Getty

Getty

There were frequent protests at fracking sites in England during the 2010s

Reform UK's Andrea Jenkyns, the Lincolnshire mayor, is also a fracking enthusiast and recently met Egdon Resources, an oil and gas firm that has licences for targeting shale gas in an area known as the Gainsborough Trough.

The company has been touting analysis by accounting firm Deloitte, which estimates that gas in the trough could be worth £140bn to the UK economy and create 250,000 jobs.

The Deloitte assessment is not public and Egdon Resources would not share a copy with the BBC.

Mark Abbott, the CEO of Egdon Resources, says the company would look to invest millions in shale gas "if the regulatory environment allowed that".

He says that "clearly Reform has a policy which is more supportive than we've seen for a while".

Star Energy Group is another company that has interests in areas with potential shale deposits.

Its CEO Ross Glover has met Reform UK councillors in Lincolnshire, where the party controls the county council.

"We know there's a world class resource there," Glover says. "I believe the UK needs whatever indigenous energy it can get, be it wind, solar, geothermal."

Energy transition

For Michael Bradshaw, a professor of global energy at the Warwick Business School, there's a feeling of déjà vu.

He's been studying fracking policies for years and says last time, the industry made no progress.

"The work carried out by the geologists in our research programme suggested that the complex geology of the shale basins in the UK would make it significantly more difficult and costly to extract," Bradshaw says.

He says the estimated expense of producing British shale may mean it would not be able to compete with cheaper gas imported from Norway or elsewhere.

As a result, Professor Bradshaw says, energy bills would not be lower in the short term.

In any case, with Labour in government, fracking is a non-starter.

Labour is focusing on building out the UK's renewable energy and is aiming for clean power to meet 100% of electricity demand by 2030.

Energy Minister Miatta Fahnbulleh says Labour was going all out to "seize the opportunities of the clean energy transition".

"We intend to ban fracking for good and make Britain a clean energy superpower to protect current and future generations," Fahnbulleh says.

"The biggest risk to our energy security is staying dependent on fossil fuel markets and only by sprinting to clean power by 2030 can the UK take back control of its energy and protect consumers from spiralling energy costs."

Although fossil fuels are expected to be a feature of the UK's energy and economic systems for years to come, their role is diminishing as countries turn to cleaner alternatives.

If a Reform government does pivot back to fracking in 2029, it might find itself out of step in a world that's trying to go green.

.png)

3 months ago

12

3 months ago

12

English (US) ·

English (US) ·